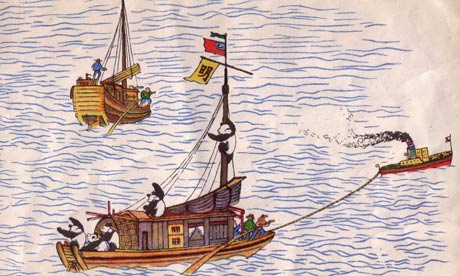

Ming and the panda hunter Floyd Tangier-Smith, as imagined by author and artist Chiang Yee in The Story of Ming. Illustration: Barbara Chiang

As the nation eagerly waits Edinburgh Zoo's announcement of the outcome of the artificial insemination of its female panda Tian Tian, it seems like an apt moment to look back on the life of Ming.

Not Flash Gordon's arch-nemesis Ming the Merciless, but Ming the first baby panda to set foot on British soil. She might not have had the flamboyant collar, forked beard or exaggerated eyebrows of the evil emperor, but she still managed to cause a massive sensation.

Ming's story begins in the wild, bamboo-clad mountains of China's central Sichuan Province, where she was born in 1937. Within a year, hunters had captured her and delivered her into the acquisitive hands of one Floyd Tangier-Smith (let's call him Tangier), a Japanese-born American who had given up banking for a life of adventure.

Tangier's desire to export pandas from Chengdu would have been adventure enough in peacetime. With the second Sino-Japanese War in full, murderous swing, it is remarkable that he succeeded at all.

Floating down the Yangtze to Shanghai was unthinkable, so Tangier arranged a gruelling road trip for the pandas: "We had to put all our cages and equipment on lorries and do a journey of 35 days to Hong Kong on roads that were often nearly impassable through bandit-infested country," he wrote.

En route, one of the trucks rolled down an embankment and a couple of the pandas escaped from their cages. "Happily they were quite willing to be caught again, and the incident led to the loss of nothing more than a day."

By the time Tangier had secured a passage from Hong Kong to London on board a cargo vessel, one of the six pandas was dead. Of those that remained there was a senior animal he nicknamed Grandma, three other adults he called Happy, Dopey and Grumpy in a nod to the 1937 blockbuster Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and the baby that would become known as Ming.

The pandas spent the voyage to Britain chained to their open cages on deck, steaming into the London docks in a raging blizzard on Christmas Eve 1938. The stress of it all seems to have been too much for Grandma, who died of pneumonia a couple of weeks later.

Tangier flogged another of the pandas to a German dealer, who took him on a whirlwind tour of the major zoos in Nazi Germany. Tragicomically, this was the animal known as Happy.

And then there were three. Tangier sold Grumpy, Dopey and the cub to the Zoological Society of London, which plucked three of China's imperial dynasties out of the bag to rechristen them Tang, Sung and Ming. So popular was the baby panda that she found her image reproduced on posters on the London Underground, in cartoons, in a series of "panda postcards", in the form of soft toys, less-than flattering hats, a travesty of a bathing suit and in dozens of television broadcasts.

Princess Elizabeth, the future Queen, was among the thousands who turned out to see Ming. Also present was Chiang Yee, a Chinese poet, author, artist and emigree, who remarked on the extraordinary numbers of people drawn to his youthful and fluffy compatriot. "There were always rows and rows of them, especially children, round her house, waiting to shake hands with her and to cuddle her," he wrote in The Story of Ming, a beautifully illustrated children's book that dramatised the panda's journey to London.

"She heard that the zoo was making a big sum of money out of her popularity." Plus ?a change. At the outbreak of war in September 1939, Ming was evacuated from London to Whipsnade Zoo but returned repeatedly to the capital throughout hostilities, a much-welcomed boost to morale.

Sung died in late 1939. Tang lasted until the spring of 1940. Ming lived on through most of the war, but as the bombs began to fall, so too did Ming's hair. This was particularly evident around her eyes, where the exposed skin had become dry and scaly. In 1943, she started walking backwards. Then, after months of slow decline, she had a sudden fit on Boxing Day 1944, banging herself against the walls and railings of her den and cutting the skin of her muzzle and face.

Ming did not recover. The cause of death, according to a cursory postmortem, could not be determined. The Times ran an obituary: "She could die happy in the knowledge that she gladdened the universal heart and, even in the stress of war, her death should not go unnoticed."

It certainly didn't for London taxidermist Edward Gerrard, who got hold of her pelt, stuffed it and took it on a lucrative tour round the country. "Ming, dead, is priceless," ran the caption to a photograph of her stuffed corpse that appeared in Illustrated magazine.

The whereabouts of her skin remains a mystery, if indeed it survives at all. Her skull, however, passed into the collection of the Royal College of Surgeons. As of next month, Ming's skull will be on display in London at the Hunterian Museum in Lincoln's Inn Field.

Source: http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2013/jun/13/ming-panda-pioneer-britain

andy williams Lady Gaga New Girl Avalanna Gigi Chao Jimmy Hoffa Ed Hochuli

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.